Mental Health

ADHD: Frequently Asked Questions

Following are the questions I see most frequently on r/adhd and several ADHD-focused Facebook groups I’m part of. For each, I’ve provided an answer that aligns with the community consensus or the latest scientific research.

I am not a doctor and this is not medical advice. Consult a doctor before beginning any new treatment.

- Do I really have ADHD or am I just lazy?

- My parent/sibling/professor/doctor says ADHD isn’t real. Are they right?

- My parent/sibling/professor/doctor says I can’t possibly have ADHD because I did well in school. Are they right?

- My parent/sibling/professor/doctor says I can’t have ADHD because I focus just fine on video games. Are they right?

- Is ADHD really a disorder? Wouldn’t it be better if society accommodated it instead of treating it like a disease?

- Is ADHD overdiagnosed?

- How do I know what medication to start on for my ADHD? - Stimulants - Non-stimulants - The process of elimination

- Are stimulants bad for your heart?

- Will I get addicted to my ADHD medication?

- Is caffeine an effective treatment for ADHD?

- Can ADHD be treated without drugs?

- What’s the difference between ADHD and ADD?

- What are some lesser-known ADHD symptoms?

- How do I know if my medication is working? What does it feel like?

Do I really have ADHD or am I just lazy?

First of all, literally every person with diagnosed ADHD has had this thought before. It’s an ADHD cliché. The thought itself is not diagnostic of ADHD or anything, just letting you know you’re in good company.

Second, we need a working definition of “lazy.” As far as I can tell, it’s neurotypical shorthand for “this person isn’t doing the thing I want them to do.” It strikes me as a little humorous to apply the term to yourself, but many of us do. With a nod to Devon Price, it seems like “laziness” falls into four categories:

- Different values. People don’t always care about the same things. If your house is messy someone might call you lazy for not cleaning it. But maybe you just don’t care—it’s not immoral to have a dirty house or anything. Sometimes the word is used more manipulatively; there are some really terrible managers out there who call their employees lazy because they won’t give up their vacation time or do free work. You might care about your job, but not enough to do it for free or prioritize it over your own life. In both cases, someone is holding up a version of you that they wish existed and saying, “you’re not like this so you must be bad.” And in both cases they’re wrong. You’re not bad. You just care about different things than they do.

- Uncertainty about how to begin. If you don’t know how to do something you’ll have a hard time getting started on it. Even if you could probably learn how by reading instructions or watching how-tos on YouTube, the task is going to feel much bigger than it really is. Intimidation may not be a super impressive reason to avoid doing something but it’s totally normal and reasonable.

- Self doubt. Even if you know how to do something, you might be so anxious about doing a good job or being criticized that you get stuck in a spiral of self doubt. This is especially true in hypercritical environments where every detail will be scrutinized—college, work, public speaking, even doing the dishes can cause anxiety if you think someone’s looking over your shoulder. Again, you might feel silly if this is your reason for being “lazy” but there’s nothing silly about it. It’s how human brains work.

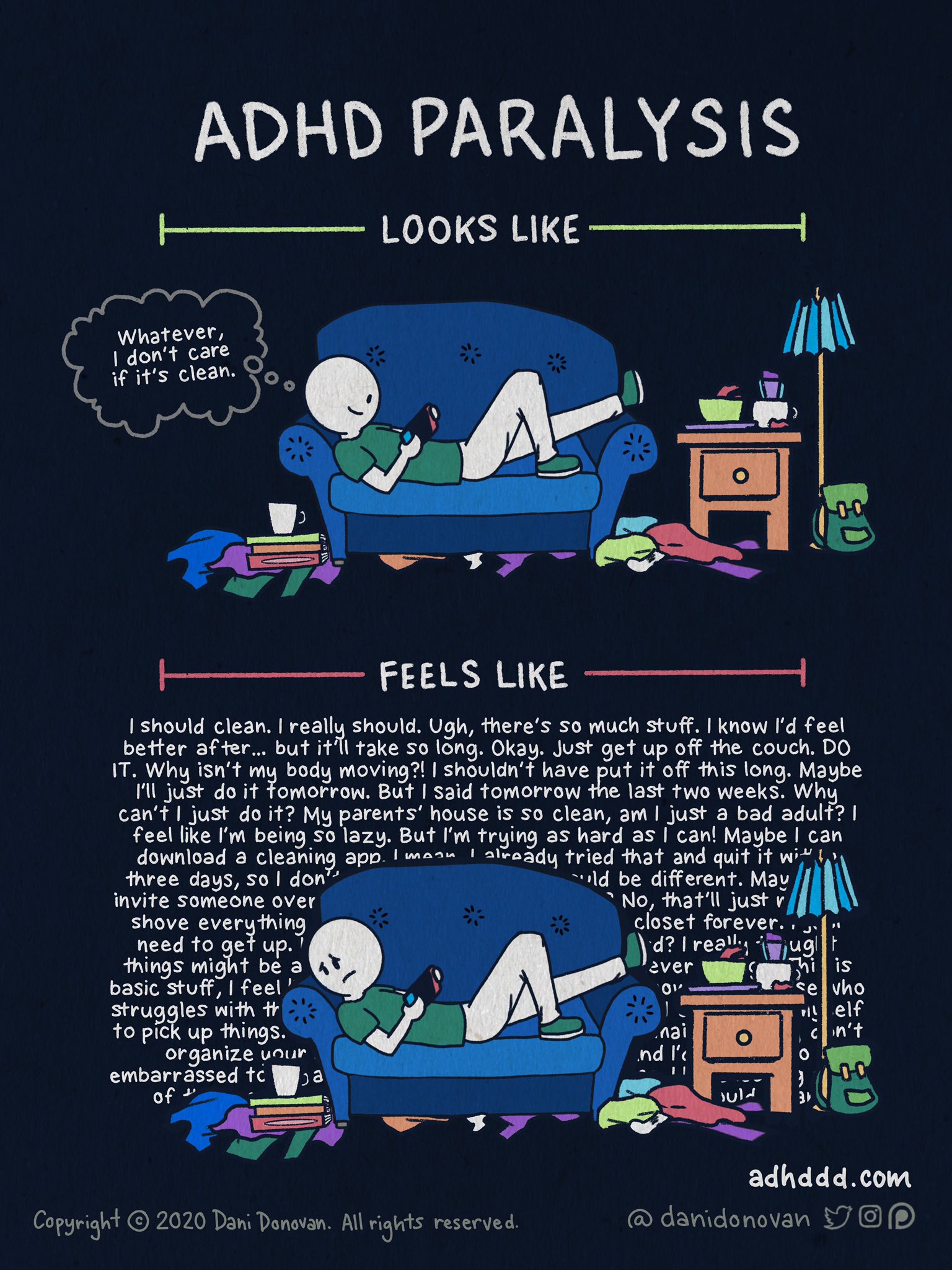

- Executive dysfunction. This is where disorders like depression and ADHD come in. Even if you care about something (a lot!), know how to do it, and are confident in your abilities, sometimes the ol’ brain just won’t get up and go. You may feel like gravity has gotten 10 times stronger, like you’re glued to the couch, or like your limbs are refusing to obey your orders. To all appearances, you’re just lazing around on your phone like you don’t care at all. But what you’re thinking is I need to get started, this is really important to me, it will only take a few minutes, why won’t my body move?? Most people experience something like this occasionally and write it off as exhaustion—but if it’s a daily thing for you, it very well may be a mental health condition.

You can decide what you mean when you call yourself “lazy.” But I’d recommend finding more specific terminology. “Lazy” isn’t a useful term, it’s a cheap shot. It doesn’t tell you what to fix. It just makes you feel bad.

Now for some bad news. There is no definitive physical test for ADHD. It’s not like diabetes or a broken leg. The doctor can’t measure your brain or take a blood sample and tell you if you have it. The diagnostic process involves talking to you about your life’s story, asking some questions about your behaviors, and checking boxes on a list of symptoms. Sometimes it also includes neurological tests to check your working memory, processing speed, and so forth. But in the end, all the doctor can do is give you their expert opinion. You may always second-guess yourself a little no matter how many second opinions you get.

People who get diagnosed later in life often have the feeling wow, this explains so much. More than anything, that’s how the diagnosis works. If ADHD explains your behaviors and struggles better than anything else, the term has done its job. If it gives you access to guidance and treatments that improve your life, so much the better. You don’t have anything to prove.

TL;DR: “Lazy” isn’t a very useful word. There’s always a reason why you’re not doing something. If that reason is “I want to do it but my brain won’t work,” the best explanation may be ADHD.

My parent/sibling/professor/doctor says ADHD isn’t real. Are they right?

No.

ADHD was first described in 1775. We’ve known about ADHD for longer than we’ve known about DNA! In recent decades we’ve been able to observe physical differences in the brains of people with ADHD: smaller prefrontal cortexes and basal ganglia, reduced metabolic rates in various areas, reduced white matter volumes, abnormal activation, abnormal dopamine transporter levels, and the list goes on. We’re not yet to the point where we can do a brain scan and definitively say if someone has ADHD. But we know enough to be certain that it exists—or as certain as you’re allowed to be in the realm of science.

The overwhelming consensus of psychiatrists, neuroscientists, and other experts is that ADHD exists. However, we can try to understand why some people deny it.

For one thing, ADHD diagnosis is quantitative, not qualitative. The experiences of people with ADHD are not altogether unique! Just about everyone has experienced forgetfulness, distraction, restlessness, losing track of time, emotional extremes, procrastination, impulsiveness, boredom, zoning out, fidgeting, hyperfocus, disorganization, and irritability. These things are part of the human experience. But not everyone experiences them in the same amount. If none of the above are a Big Problem for you—and if you haven’t had to structure your entire life around managing them—then you probably don’t have ADHD. On the other hand, if you feel like I’ve just summed up your whole personality…mmm you should consider getting a diagnosis.

Like my therapist once said: every human being pees every day, but if I told you I was peeing 100 times a day, you’d tell me to see a doctor.

Still, peeing is a universal experience. So it’s almost understandable that someone could read a list of ADHD symptoms and say “what? That’s not a disorder, that’s life! Get over it!” And either that person doesn’t understand the difference between “a little” and “a lot” or they too have ADHD, but have decided everyone else struggles with that stuff too and just doesn’t talk about it. It’s an easy trap to fall into.

The other tricky thing about ADHD is that the first-line treatments are all stimulants. Drugs like Adderall and Ritalin are frequently abused by neurotypical people to get high or “get ahead” in work or school. There are definitely some people out there who “fake” having ADHD in order to get a stimulant prescription. This doesn’t mean that everyone with ADHD is faking it. Stimulants are prescribed before anything else because they work. They increase the dopamine in your brain, they help you be more productive and focused, they help you lead a more normal life. Unfortunately, a person’s response to stimulants is not diagnostic; even neurotypical people may get benefits from them at normal doses.

So, again, it’s almost understandable for a person to say “hey, wouldn’t we all like to be taking amphetamines every morning! Sounds like cheating to me.” And again, that person either deeply misunderstands ADHD or has been shoving their own ADHD under the rug their whole life.

It’s worth noting that ADHD has a strong genetic component, so if someone in your own family ridicules or doubts your ADHD, there’s a good chance they have it too. Sometimes your own scars are the hardest to see.

TL;DR: There are a few reasons why someone might think ADHD is fake. But they’re wrong. ADHD is real, and we have over 200 years of scientific history to prove it.

My parent/sibling/professor/doctor says I can’t possibly have ADHD because I did well in school. Are they right?

No.

ADHD is not correlated with intelligence in any way. Statistically, people with untreated ADHD are more likely than their neurotypical peers to struggle in school. But you can’t apply this to every individual case. If you did well in school and it was easy for you, it’s less likely that you have ADHD—your psychiatrist would take this into account along with the rest of your personal history when assessing you. But good grades can be the end result of many different journeys.

I somehow graduated from college undiagnosed, untreated, and cum laude. But my journey involved zoning out in every class I ever attended, giving up a normal social life so I could do homework every spare minute, waking up frantic at 4 AM to finish 12-page papers, sprinting across campus more often than any person reasonably should, using multiple apps and color-coded folders just to stay organized, and crying in empty soccer fields. And I’m smart. Not the smartest person you know, but quite a bit smarter than average when it comes to textbooks and essays and exams.

Sorry! I’m fully aware that everyone who talks about how smart they are is literally the most annoying person alive. I promise not to bring it up again.

Sure, college is hard for everyone. But I could tell my experience was different from most others. There are people who would claim I don’t have ADHD because “nobody with ADHD could graduate college.” This is false. Many ADHDers have degrees, even advanced degrees, generally thanks to a combo of medication and intense compensatory strategies. You want to know my strategy? Generalized anxiety disorder. This is actually a fairly common story among high-achieving ADHDers. I was so anxious about keeping my scholarship, and my self-worth was so tied up in my grades, that I careened through eight semesters on pure angst. My mental health took some long-term damage on that one. But hey, I have an English degree now.

Your story may look different from mine, but the point is that your grades don’t say anything about how much you struggled in school. And they certainly can’t say whether you have ADHD.

TL;DR: Lots of people with ADHD get good grades. Lots of people with ADHD get bad grades. Your grades are not a diagnosis.

My parent/sibling/professor/doctor says I can’t have ADHD because I focus just fine on video games. Are they right?

No.

ADHD is often misunderstood in this regard. ADHD isn’t a complete inability to pay attention to anything, ever. It’s an inability to regulate attention. Sometimes this means paying attention to the lights or background noise when you should be listening to someone speak; other times it means getting so excited about a task or hobby that you lose track of time and the whole world disappears around you (that’s what we call hyperfocus).

Some things are particularly good candidates for hyperfocus. Video games and social media, for example, are designed to be addictive even for neurotypical brains. For someone with ADHD they’re especially so.

An important factor in attention is interest. Neurotypical people can, with effort, pay attention to something they’re not interested in. People with ADHD usually can’t, at least not for long. And that’s only the tip of the iceberg. Even if something is interesting and important, an ADHD brain may decide that a ceiling fan, a spider on the wall, a television screen, a pile of gravel, the sky, or an idea it just came up with is even more interesting. Interest isn’t a voluntary thing, unfortunately.

So attention in ADHD isn’t so much a matter of scarcity. It’s a matter of control.

By the time we reach adulthood, a lot of us have figured out ways to pay attention when we need to—but many of these, paradoxically, make it seem like we’re not paying attention at all. Fidgeting, for example, is a popular way to give our brains something to do without giving them too much to think about. It may look like boredom when we play with our hands or jiggle our legs, but it’s really a focus aid. Some of us close our eyes or stare at the floor when we’re really trying to listen, since that gives our brain less points of interest to get distracted with. Some days it’s easier to focus, some days it’s harder. And even in the best of circumstances we may need a few extra moments to respond to something, since it takes time to bring our mind back into the room when it gets away from us.

TL;DR: ADHD means you can’t control your attention, not that you don’t have any attention at all. Most people with ADHD can focus on something they enjoy.

Is ADHD really a disorder? Wouldn’t it be better if society accommodated it instead of treating it like a disease?

This is wishful thinking, but it does raise some important points.

There are two main models of ADHD—that is, two different ways of describing it. Both of them are useful in the right context.

The medical model describes ADHD as a collection of symptoms which can (ideally) be treated so their effect on the patient is reduced. The social model describes ADHD as a form of neurological diversity—the result of natural variations in human brains. Under the medical model, the person with ADHD should be treated, cured if possible. Under the social model, the structures and expectations of society should change to allow the person with ADHD to thrive.

The medical model has allowed us to develop medications and therapeutic methods that help significantly with many ADHD symptoms. Even with plenty of support and accommodations, a lot of people with ADHD take medication and/or meet with a therapist. There’s just no substitute for professional help and a steady supply of neurotransmitters.

The social model, meanwhile, has helped spread acceptance and awareness of ADHD. Most people know what it is and understand, at least implicitly, that it’s not a moral defect or something to be mocked. These days there are plentiful materials available to educate teachers, relationship partners, and managers on the best ways to accommodate people with ADHD and help them succeed.

Some people think that enough education will eventually create a world where people with ADHD don’t need to be treated. But even in an ADHD paradise—a place where we could always engage our interests without any external expectations—executive dysfunction would still be difficult to manage. And a world like that isn’t practical anyway.

As always, it’s important to listen to the people we’re trying to help. The ADHD community is overwhelmingly in favor of both medical and social approaches to improving the lives of ADHDers. It’s not helpful to focus on one of those approaches so much that we ignore the other.

TL;DR: There are some things the world can do to accommodate ADHD, but therapy and medication will never become unnecessary.

Is ADHD overdiagnosed?

Possibly, but not likely.

People point to increasing ADHD diagnoses over the years as evidence that the diagnosis is being handed out like candy. Sometimes they judge estimates of the prevalence of ADHD—up to 10% of children and 5% of adults, depending on the source—to be outlandish: “there’s no way so many people have ADHD!” And admittedly, sometimes it seems half the people on TikTok have ADHD. (Wait, you mean the world’s most addictive app is disproportionately used by the world’s most addiction-prone people? Outrageous!)

These finger-in-the-wind checks do not carry the weight of science. But as with any condition, there is definitely a risk of misdiagnosis. ADHD has several traits in common with autism, bipolar disorder, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and some learning disorders. And there’s no promise of exclusivity here—it’s very common to have ADHD and one or two other conditions. Many people who are diagnosed as adults originally had a different diagnosis. And inevitably, some people will be diagnosed with ADHD when they really have something else.

It’s good to ask questions and hold science accountable. But the danger here is in teaching people that ADHD is some overhyped trend. This could lead to people with legitimate diagnoses (read: most people with ADHD) being subject to skepticism and having to worry about being believed when they talk about their needs.

The harms of misdiagnosis are that a person could receive treatment they don’t need, spend money unnecessarily, or be stigmatized by a label that doesn’t really apply to them. None of this, one would hope, is life-ruining stuff. But it is something we should work to avoid. The solution to these problems is for doctors and other experts to create and adopt better standards for diagnosis. In some places it’s still possible to get an ADHD diagnosis during a half-hour visit with your primary care doctor, which doesn’t inspire a lot of confidence.

However, when it comes to ADHD diagnosis, the much larger concern in the community is underdiagnosis. In childhood, girls are diagnosed with ADHD three times less often than boys. Black, Hispanic, and Asian people are diagnosed with ADHD less often than white people. In countries without universal healthcare, poor people often don’t have access to a diagnosis, and in countries with universal healthcare, local shortages of psychiatric professionals can lead to wait times of months or years before a diagnosis can be obtained. In some countries, ADHD is not well-understood and/or ADHD medication is illegal. There’s no evidence that ADHD discriminates by gender, race, class, or geography, so all of this is concerning.

The harms of undiagnosed or untreated ADHD are severe. People with untreated ADHD are far more likely to develop life-threatening addictions, engage in risky behavior, struggle with jobs and relationships, and be incarcerated. Untreated ADHD has been found to reduce life expectancy by ten years or more. So if we’re being reasonable, underdiagnosis is a far more damaging than overdiagnosis.

TL;DR: It’s easy to confuse ADHD with another disorder and the diagnosis process can be improved. However, underdiagnosis is a bigger problem than overdiagnosis.

How do I know what medication to start on for my ADHD?

I am not a doctor and this is not medical advice. Consult your doctor before beginning any new medication.

There are two types and four classes (five, by some counts) of ADHD medications.

The two types are stimulants and non-stimulants. In very rare circumstances your doctor may recommend otherwise, but almost always you should begin with a stimulant. Stimulants are the most effective drug for ADHD and generally have the best response.

Stimulants

The two types of stimulant are methylphenidate (e.g. Ritalin) and amphetamine (e.g. Adderall). Both of these come in several different forms. Ritalin and Adderall themselves are instant-release medications, which means the whole dose you take will affect you almost immediately. They wear off in a few hours, at which point you can take another one. There are also extended-release formulations of both of these: Concerta is extended-release Ritalin and Adderall XR is extended-release Adderall. These are intended to last most of the day. Many people prefer the extended-release drugs so they don’t have to remember to take a pill two or three times a day. Vyvanse is another extended-release amphetamine drug that’s very popular (but it’s also more expensive than the others I’ve mentioned because the patent doesn’t run out until 2023). And then there are a few other variations of methylphenidate and amphetamine: liquid formulas, dissolving lozenges, skin patches, slightly different molecules, and extended-release pills that last different amounts of time. The basic ingredients are the same, but the different delivery mechanisms can help you find something that works best for your brain and routine.

There are a few studies suggesting that methylphenidate works better for children and amphetamine works better for adults. But it may be a good idea to try both and see if one works better for you.

Some people experience positive effects on their very first day with a stimulant. Others have to take them for a few days to notice the benefits. In either case, the effect wears off within a day and the drug leaves your system entirely in a few days, so if you don’t like it you can stop taking it without long-term consequences. Some of the initial side effects (like loss of sleep and feeling jittery) tend to subside over time, so don’t assume that your initial response is how you’ll always feel.

One inconvenient thing about stimulants is that they’re controlled substances in the U.S. and illegal in many other countries, so the laws around prescribing and obtaining them can be overbearing, involving repeated doctor’s visits, phone calls, delays, and obstacles—decidedly an ADHD-unfriendly experience. Since they can be abused to get high, they’re also a theft risk; you might want to avoid telling people you have them.

Non-stimulants

The two types of non-stimulant are SNRIs and alpha agonists. Like anti-depressants, SNRIs can take weeks to fully kick in and weeks to fully leave your system. However, if stimulants don’t work for you or have too many side effects, non-stimulants like Strattera, Qelbree, and Wellbutrin can be promising options.

Alpha agonists Kapvay and Intuniv are drugs traditionally prescribed to treat high blood pressure. However, they’ve also been found effective for ADHD.

None of these are controlled substances, so they should be available almost everywhere and relatively easy to obtain.

The process of elimination

You might be lucky enough to find a drug that works well for you on your first try. However, it’s also common to have to try several different ones before you’re fully happy. Generally you’ll need to titrate: start at the smallest dose of a given drug, then increase the dose gradually until either it starts working or the side effects become unmanageable.

There unfortunately is no genetic test or health indicator that will tell you what drug is best for you. Your doctor or psychiatrist may have opinions about how different drugs work or who they work best for, but those opinions tend to be speculative. Finding the right medication is a crapshoot. You really just have to go with your gut.

The process of trying and titrating different drugs until you find a perfect match can take years. And even with a really good fit, some days your brain will just not work like you want it to. What’s worse, it’s not unheard of for someone to discover after several years that their prescription is no longer effective and have to start the process over. All this can be discouraging. But the benefits of medication are worth the trouble for many of us.

A (nearly) complete list of approved ADHD drugs can be found here.

TL;DR: Talk to your doctor. Usually you should start with a long-acting stimulant: Adderall XR for adults, Concerta for kids. If those are no good, keep trying different ones until you find something that works.

Are stimulants bad for your heart?

No.

Many, many studies have been done on this subject. Since stimulant medication is known to increase blood pressure and heart rate, it’s natural to assume that it will strain the heart. However, no evidence has been found of increased heart attacks, sudden death, or strokes, except in new users over the age of 65.

I’ve done a literature review on this subject which you can read if you want to learn more: Stimulant medication and heart health.

Will I get addicted to my ADHD medication?

It’s very unlikely, especially if you take it exactly as prescribed.

People with ADHD have lots of complaints about their meds. There are side effects, some days they don’t seem to be working, and they don’t treat all the symptoms of ADHD. Some people feel that the drugs change their personality or that the “crash” (the effects felt when the drug wears off) isn’t worth the benefits. Many people take “medication holidays” on weekends or even more often, either because they’re sick of their meds or because taking a break seems to make them work better. And just about everyone forgets to take their medication sometimes.

If we wanted to qualify as “addicts” we’d have to try a lot harder than that.

Interestingly, several studies have found that children with ADHD who take stimulant medication are less likely to develop drug addictions later in life. People with ADHD are prone to addiction, possibly due to chronic understimulation, so it makes sense that proper treatment would reduce that risk. Anecdotally, several people with ADHD have reported that medication has helped them reduce or quit various addictive behaviors.

Stimulants do trigger the brain’s “reward circuit” which is a factor in addiction. But at the doses ADHD medications are prescribed at, the risk is minimal.

TL;DR: It’s not something you should worry about. Make sure not to take more than your prescribed dose.

Is caffeine an effective treatment for ADHD?

Sometimes.

Everyone responds differently to caffeine. You might find that a few cups of coffee really help you focus, or you might find that they just make you jittery and restless. If it works for you, go for it. Caffeine is cheap, tasty, and easy to get.

Keep in mind that caffeine hasn’t been found as effective for ADHD as prescription medications. And you’ll need to be careful with the dose—yes, it’s possible to overdose on coffee, even moreso on energy drinks or caffeine pills. But if a couple hundred milligrams gets you on your way, then congratulations, you have the most easily treatable ADHD of all time.

Make sure to test the waters gradually. Regular caffeine use can develop into dependence, which isn’t as bad as addiction (yes, they’re different, look it up) but can still mean hellish withdrawals if you want to (or have to) stop caffeinating, even just for a day or two. I’ve had some terrible withdrawals from caffeine; I’ve had basically zero withdrawals from prescription stimulants.

TL;DR: It works for some people, not so much for others. Watch out for withdrawal headaches.

Can ADHD be treated without drugs?

Pharmaceutical drugs are the most effective and successful treatments for ADHD. Most people’s concerns about them aren’t justified. Still, they don’t work for everyone, and even when they do they work best in combination with other techniques.

- Therapy (such as CBT) can help you develop techniques to manage your ADHD symptoms.

- ADHD coaches specialize in helping ADHDers get control of their lives and accomplish goals.

- Exercise is almost always helpful, since it releases dopamine in the brain.

- Many ADHDers report positive results from eating more protein.

- Calendar and reminder apps can be indispensable.

- Some evidence indicates that Omega-3 supplements may be helpful, though more research needs to be done.

- Neurofeedback isn’t well-researched, but some evidence indicates that it may be helpful.

- Meditation isn’t a cure and many people with ADHD find it excessively difficult, but others find it helpful.

Be wary of anyone selling supplements, oils, brain scans, or therapeutic techniques outside of the above. Always look for multiple studies and articles in respected publications before spending your money on a non-mainstream treatment. Do your research and don’t get scammed.

Some people will tell you to “just try harder” or “buy a planner.” These are not effective ADHD treatments.

TL;DR: There are multiple effective approaches to ADHD treatment. The best ones include medication.

What’s the difference between ADHD and ADD?

“ADD” is no longer a medical diagnosis. The term was retired in 1987. What we used to call ADD is now called “ADHD - Primarily Inattentive.” It’s one of three presentations of ADHD, the other two being “ADHD - Hyperactive/Impulsive” and “ADHD - Combined Type.”

Your ADHD presentation is determined by your symptoms. The treatments are the same for all three.

ADHD - Primarily Inattentive type is characterized by distraction, carelessness, forgetfulness, boredom, and disorganization.

ADHD - Hyperactive/Impulsive type includes symptoms of restlessness, fidgeting, lack of focus, talking or moving too much, trouble staying seated, interrupting, acting impulsively, and not being able to wait for one’s turn.

ADHD - Combined Type is diagnosed when you have several symptoms of both of the other types.

No subtype can completely describe what ADHD is like for someone. Every individual’s experience is unique. And many of the greatest struggles of ADHD can’t be found in official materials at all; the diagnostic manual seems to have fallen well behind the community’s understanding. Still, the ADHD label helps us find support, identify with others, and get the treatment we need.

TL;DR: “ADHD” is now the preferred term for all attention deficit disorders, including what we used to call ADD.

What are some lesser-known ADHD symptoms?

Describing something not found in the DSM (the diagnostic manual for mental health disorders) as an “ADHD symptom” can be tricky business. The diagnosis of ADHD doesn’t rule out other disorders, personality traits, or normal everyday problems.

For example, more than half of people with ADHD will have depression at some point. Anxiety is just as common. Neither of these are ADHD symptoms, but with those numbers they might as well be! People often find that when they get the treatment they need for their ADHD, the anxiety and depression start to subside.

Another common experience in ADHD is rejection sensitive dysphoria, or RSD. This is an intense fear of being disliked or rejected that can manifest as social anxiety, social phobia, people-pleasing, poor self-esteem, being easily upset or embarrassed, or reluctance to open up to others. The vast majority of people with ADHD are more sensitive to social rejection than their peers, and many say that RSD is the single most difficult symptom of their ADHD. It’s hard to say whether RSD is an inherent symptom of ADHD or simply the result of a lifetime of harsh criticism and social rejection, but its association with ADHD is undeniable either way.

Other things that people in ADHD circles often bring up and bond over include:

- Serial obsession. ADHDers will get interested in a subject or hobby, devote themselves passionately to it for days or weeks, and then leave it behind forever. It’s fairly common to find them surrounded by old craft supplies, half-read books, exercise equipment, abandoned projects, and planners.

- Disordered eating. Some ADHDers have trouble preparing food or remembering to eat and end up undernourished. Others use food as a source of dopamine and start to believe that they weigh too much or are hopeless overeaters.

- Underperformance at school and work. Some ADHDers develop routines and coping mechanisms that allow them to succeed in high-expectation environments. Others have very severe symptoms or a lack of support that make this impossible (or nearly so). It’s common for people with ADHD to have a long history of getting fired from jobs, failing classes, and being written off as hopeless.

- Chronic lateness, earliness, or absence. ADHD causes reduced executive function. One effect of that can be time blindness, an inability to know how much time has passed or estimate how long something will take. This can result in being late for everything, or a person may overcompensate and be way too early for everything. Another effect of reduced executive function is forgetfulness: without a timely reminder, a person with ADHD may not remember to show up at all.

- Thrill-seeking. Adrenaline is a pretty good substitute for dopamine in a pinch, and some ADHDers use high-stakes activities like extreme sports, illegal drug use, and sex to get the neurotransmitters they desperately need.

- Body-focused repetitive behaviors or BFRBs. Doing things with your body like fidgeting, hair pulling, skin picking, nose picking, nail biting, leg jiggling and so on is a habit many ADHDers are familiar with. These are coping mechanisms that can release dopamine and help with focus. Many ADHDers are self-conscious about these behaviors because they sometimes annoy others.

- Restless Leg Syndrome and insomnia. Many people with ADHD struggle to keep a healthy sleep schedule—they can’t fall asleep quickly, they wake up frequently during the night, they sleep too late, or they feel sleepy during the day. There’s also an association between ADHD and Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS), the intense feeling of needing to move or twitch your legs when you’re trying to fall asleep.

- Compulsive social media usage. Social media apps like Facebook and TikTok are addictive by design, and ADHDers may find themselves spending excessive amounts of time on them.

- Dyscalculia, dyspraxia, and dyslexia. Some ADHDers have an abnormal amount of trouble doing simple math (dyscalculia), are clumsy and lose their balance a lot (dyspraxia), or have trouble reading (dyslexia).

- Auditory processing issues. ADHDers may have trouble understanding what other people are saying, especially in music and TV or anywhere there’s a lot of ambient noise, and may be sensitive to loud or droning noises. Other sensory processing issues can also exist in ADHD, like intense sensitivity to clothing tags or the textures of certain foods.

- Autism. Autism and ADHD overlap significantly and a lot of people have both.

With a disorder as widespread as ADHD, almost any experience will be shared by some of us. We have to be careful not to ascribe our entire personalities and every uncomfortable experience we’ve ever had to the disorder. ADHD isn’t responsible for worn-out socks, diarrhea, dad jokes, or a hatred of country music. ADHD is part of who we are and what we struggle with. It may even be a big part. But we’re still individuals.

TL;DR: Anxiety, depression, and fear of being disliked are extremely common. Many other experiences are common in ADHD as well. It’s hard to say which ones are direct symptoms.

How do I know if my medication is working? What does it feel like?

You may not feel any different, at least at first! You will, however, notice that you’re able to pay attention when other people are speaking, you have less trouble getting started on boring or difficult tasks, you have the energy to do normal-adult things like clean and cook, and you’re calmer and less overwhelmed. You might have to pay close attention over the course of a few days to realize the difference.

Some people’s first day on stimulant medication is a revelation. They feel incredibly focused, energetic, and capable—they may even experience a small high. This will subside a bit (the high will go away completely) over the next few days as their body adjusts to the medication. But even over the course of months, medication should have a positive effect on your ability to meet the challenges of life. It’s not for getting high, it’s for doing the things you need to be able to do.

The first medication you try might not be a perfect fit. Luckily there are lots of drugs available, and your doctor can help you try different ones until you find the right prescription and dosage.

TL;DR: If you’re able to get things done and cope with life, it’s working.