Self

On body weight

Content Warning: fatphobia, dieting, eating disorders, medical discrimination

The New Year is coming up. Some of you are about to make harmful, unscientific, doomed resolutions, treating your body like Intel treats a microchip—that is, trying to make it smaller and smaller year after year.

In Western society, pervasive messages about body size teach us that being small means being worthy, healthy, desirable, motivated, in control; and that being large means being lazy, sick, stupid, secondary, an eyesore. All of these things are false. Yes, even the “healthy” one. I’ll shine the light of science on that presently, but in the meantime take a moment to examine the way this paragraph has made you feel. Doubtful? That’s understandable, since the science on this has evolved significantly over the past decade and you’ve spent a lifetime in a world that determines a person’s worth by their weight. Skeptical? You should be. This is the Internet. Offended? Sounds like you’ve tied your self-esteem to your body, and I can’t emphasize enough how poorly that will serve both your self-esteem and your body.

I am fat. Anyone who hasn’t seen me since 2009 would be shocked. I was one of the thinnest people in my high school and I didn’t start gaining weight until several years later. I now weigh about 275 pounds. Even at a towering 6 feet 6 inches tall, that’s fat.

Here’s a quick rundown of things you may be tempted to say and why you shouldn’t say them:

- Oh, sweetie! You’re not fat! And what if I could prove that I am? Is that such a horrifying idea that you can’t even permit it to enter your mind? I literally have a body mass that significantly exceeds the median for people of my height. I didn’t say I was bad or worthless, I just said I was fat. “Fat” is not a bad word or a putdown.

- That’s not healthy. You know nothing about my health. Zero. Zippo. Weight is not health, and I can produce study after study to prove it. And even if you somehow got ahold of my bloodwork and minute-to-minute footage of my lifestyle, it wouldn’t be your job to care unless you were my doctor or my wife. What you’re doing is called “concern trolling” and has way more to do with your insecurities than my well-being.

- Whenever I start to get overweight, I cut carbs for a couple months until I’m back to normal. What you’re doing is called “weight cycling” and it’s associated with equal or greater health risks than obesity itself. What you are doing is not healthier than being fat.

- Calories in, calories out. It’s simple math. Cool, you’ve shown us that you understand addition and subtraction. If you also understood the psychological, physiological, and genetic factors affecting body mass, you’d really have something.

Now that we’ve got some of the fatphobia out of the way, can we talk science?

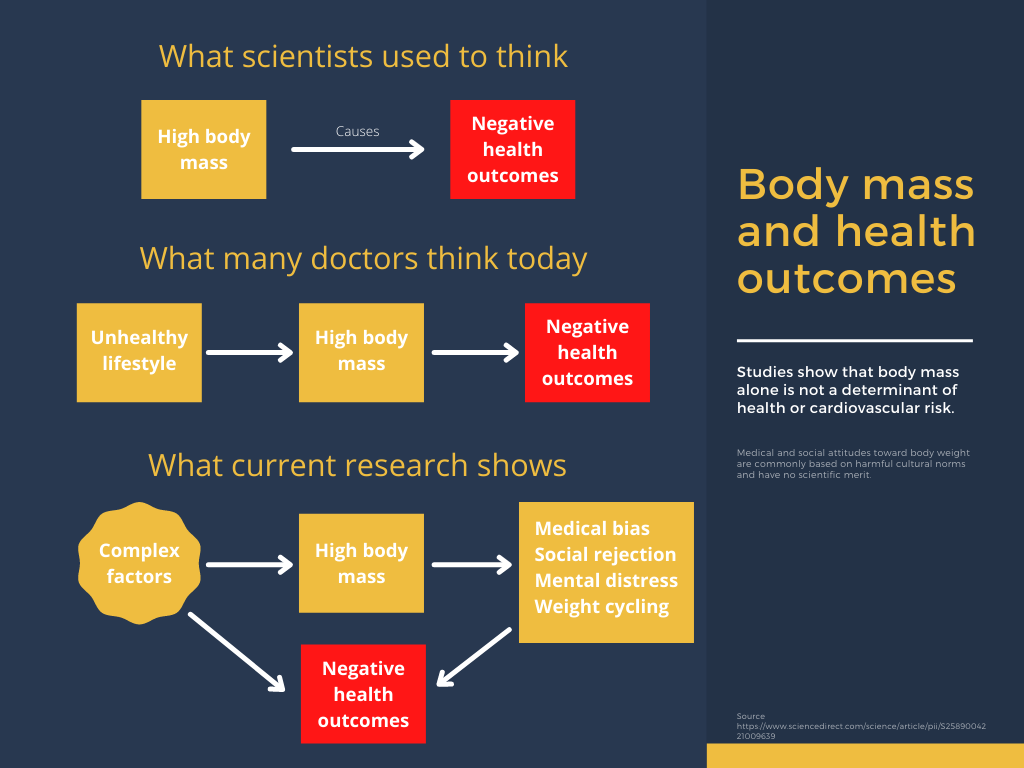

Most people have a rudimentary and obsolete understanding of the health consequences of one’s weight. Here’s an infographic that describes how research about body weight has changed over the last several decades:

Source: original content. Supporting data taken from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589004221009639.

You may wonder, if weight is not directly a driver of health outcomes, why such strong correlations have been reported in the literature. There are indeed decades of medical guidelines indicating that overweight people are more likely to have heart attacks, strokes, or diabetes. But this is a mere correlation, and we should apply the same skepticism here that we apply to all correlations: does A cause B? Does B cause A? Does a third, unstudied factor cause them both? Or do they just trend together by chance?

A related, very interesting correlation is that as weight-loss attempts have risen over the past 40 years, so has obesity. Most researchers reverse the phrasing here, but the cause-and-effect likely goes both ways. Weight-loss attempts almost always fail and very often result in overall weight gain. And convincing people they need to lose weight is a 72 billion dollar industry in the United States alone. Therefore we should assume that some proportion of obesity is driven by weight-loss attempts. To be clear: some people are fat because a powerful economic engine convinced them to try very hard not to get fat.

To answer that question, let’s start with the most common hypothesis: that overweight people have negative health outcomes because they are overweight. If this were true, we could illustrate it by designing a study where we put people randomly into two groups. We’d work with Group A to help them lose weight and we’d leave Group B the hell alone. By the end of the study we’d expect people in Group A to weigh less and experience fewer negative health outcomes than Group B. As luck would have it, this exact study has been performed a hundred or so times. The results are extremely boring: “Overall, data from observational studies and RCTs [randomized controlled trials] do not consistently show that intentional weight loss is associated with reduced mortality risk.” In other words, Group A loses weight but doesn’t live longer.

Another deficiency of the above hypothesis is that, as the data has it, moderately overweight people are the least likely to die out of all weight ranges. This raises the question of what exactly “over” is doing in the word “overweight.”

The death knell for this hypothesis is the fact that overweight people with good cardiorespiratory fitness, or CRF, are at least two times less likely to die than median-weight and underweight people with poor cardiorespiratory fitness. Studies that control for CRF find that body weight is largely irrelevant. And since increased CRF does not generally result in weight loss, any attempt to tie body mass directly to health is left without a leg to stand on.

Suppose you want to lose weight anyway (or someone else wants you to). Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be any way to do that—not if you’re looking for something with a probability of success higher than five percent. Commercial programs don’t work. Diets don’t work. Exercise doesn’t work. Medications and surgery exist, but these are only recommended for abnormally high-risk cases—and even then it’s not certain whether they’ll improve your health (they certainly won’t improve your CRF).

So in summary:

- Being fat doesn’t make you unhealthy.

- Fat people are often healthier than thin people.

- Losing weight doesn’t make you healthier.

- There is no broadly effective way to lose weight.

- Exercising makes you healthier, but doesn’t make you lose weight.

And even if we were to cast all this aside, fatness would still be morally neutral. Obesity has been correlated to many factors—notably genetics, poverty, and ADHD—but it has never been correlated to a person’s worth, their success in life, or the way they treat others.

At this point a reasonable person might still have a few objections to the argument I’m making.

First, I refer heavily to one published paper, which a casual observer might not consider strong evidence against a long history of medical guidelines that vilify fatness. On closer observation you’ll notice that this paper is a meta-analysis of meta-analyses. Scores of individual trials and studies are represented in the results. This is not a single study; it’s a synthesis summarizing the state of the art when it comes to obesity, fitness, and health.

Second, the authors of the paper bring up multiple studies that seem at odds with my (and their) conclusions. They also don’t frame their conclusions as strongly as I do. Both of these things are common in high-quality research. Acknowledging all the available data, rather than ignoring studies that disagree with them, strengthens their position overall. And good scientists are careful to avoid overstating their results. These are a few indicators (of many) that their conclusions are sound:

… a weight-centric approach to obesity treatment and prevention has been largely ineffective. … A weight-neutral approach to treating obesity-related health conditions may be as, or more, effective than a weight-loss-centered approach, and could avoid pitfalls associated with repeated weight loss failure. … Epidemiological studies show that CRF and PA [physical activity] significantly attenuate, and sometimes eliminate, the increased mortality risk associated with obesity. More importantly, increasing PA or CRF is consistently associated with greater reduction in risk of all-cause and CVD mortality than intentional weight loss.

Third, the correlation between high body mass and negative health outcomes remains an unsolved mystery, since a slight difference remains even when CRF is controlled for. Sociological complexity in this space is more than likely sufficient to explain that difference. For example, overweight people are more likely to:

- Develop an eating disorder as a result of social pressures

- Be victims of medical bias from doctors who are phobic of fat people

- Suffer from anxiety and depression due to preoccupation with weight

- Be rejected for jobs because of implicit bias

- Be bullied at school

- Experience social rejection throughout adolescence and adulthood

Each of these is known to have negative health consequences. It’s hard to isolate social effects in a scientific study, but when these factors are taken into account it casts a very harsh light on researchers’ assumptions as to the reason for health disparities in overweight people.

Some may look at a list like this and think all the more reason to avoid being overweight. But that’s blaming the victim. Fat people are not responsible for the way other people respond to their bodies. The fault here is not with overweight people but with cultures that villainize body fat, and specifically those who profit from doing so. Society has naively allowed body weight to become a widely-accepted inverse proxy for desirability and worth, and in doing so has stifled our ability to fairly examine what (if any) relationship weight has to health.

I maintain that such a relationship is hallucinated, and I believe the evidence bears that conclusion out. A greater skeptic might say there isn’t enough evidence one way or the other. In any case, it’s clear that a culture oriented around weight loss is operating outside the realm of established truth, responding to incentives that are ultimately harmful, and blaming overweight people for problems they are not responsible for (and that may not even exist).

So a New Year’s resolution to lose weight, besides being uninteresting and almost guaranteed to fail, isn’t beneficial to you or anyone else. May I suggest some better ones:

- Throw away your bathroom scale.

- Read the excellent book Intuitive Eating by Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch.

- Find a cardiovascular activity that you truly enjoy and fit it into your schedule. If you’re moving your body, it counts.

- Try a new recipe or cuisine.

- Find a way to care for your body that doesn’t involve weight or size. For example, adopt a skin care routine.

- Throw away or donate any of your clothes that don’t fit or make you feel insecure.

- Examine your internalized fatphobia and deconstruct it, possibly with the help of a licensed therapist.

These things won’t make you smaller. (Or they might: bodies change all the time and that’s okay.) But they will improve your life.