Technology

Diagonals of two-dimensional arrays

Today I had an interesting problem to solve. For a given two-dimensional array (or matrix), I needed to construct some efficient views into the data from multiple angles.

Rows!

final List<List<int>> rows = [

[1, 2, 3, 4],

[5, 6, 7, 8],

[9, 10, 11, 12],

];

This is an example of the data I was starting with. You might call it an “array of rows.” In terms of tabular data, the indices of the outer array are the rows, and the indices of each inner array are the columns. Ignore that for now; the code block says it best.

Another way to describe this is a horizontal view. Since the data in its canonical form already fits this view, let’s check that off.

✅ Horizontal view

Columns!

The next thing I needed was a vertical view.

// Desired output

[

[1, 5, 9],

[2, 6, 10],

[3, 7, 11],

[4, 8, 12]

]

This array contains the same data, but in inverted access order. The indices of the outer array are the columns, and the indices of each inner array are the rows. The code block no longer looks like the data! In Dart, constructing this view is easy:

import 'package:collection/collection.dart';

final Iterable<Iterable<int>> cols = IterableZip(rows);

IterableZip is often just called zip in other languages (or their respective functional programming libraries). It accepts a list of two or more iterables (a.k.a. enumerables or lists), then on each iteration N, it emits the Nth element of each iterable, all packed together in a new iterable. Lazy evaluation keeps this lightweight and efficient.

✅ Vertical view

Eldritch horrors!

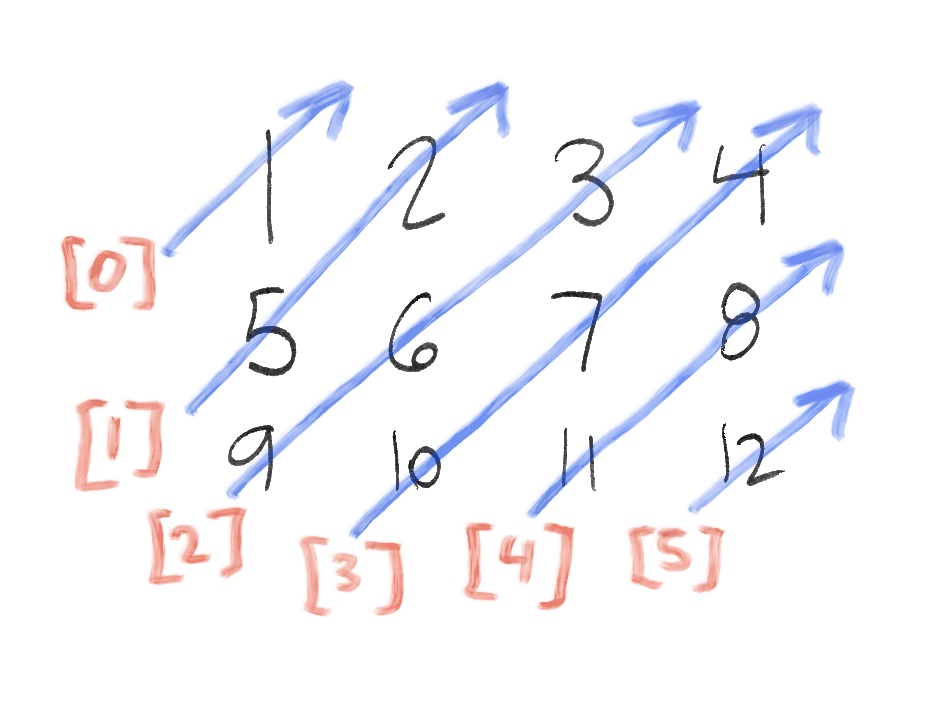

The last thing I needed was a diagonal view (…dear god). Like this:

Or, as a code block:

// Desired output

[

[1],

[5, 2],

[9, 6, 3],

[10, 7, 4],

[11, 8],

[12]

]

This turned out to be a bit of a head-scratcher. (I’m sure a mathematician could solve it instantly, but I’m not one of those.) The first thing I needed to do was consider how the diagonal view corresponded to the original data—how the coordinates of the original would be transposed.

// Desired output, in terms of coordinates

// from the original data

[

(0, 0)

(0, 1) (1, 0)

(0, 2) (1, 1) (2, 0)

(1, 2) (2, 1) (3, 0)

(2, 2) (3, 1)

(3, 2)

]

I stripped out some of the symbols to make this easier to scan.

Wow. Kind of beautiful, isn’t it?

My first epiphany was:

All the coordinates on each diagonal have the same sum, and that sum is the index of the diagonal (in the array of all diagonals).

So if you know how many diagonals there are, you can simply write a loop, and your index in the loop will tell you what each set of coordinates needs to sum to.

That’s great, but sums are destructive. How do you know which numbers to use, out of all the numbers that add up to your target?

Well, for the first few diagonals, you can just calculate all possibilities: start iterating at 0, count up to the sum, and then stop. For each iteration, your index in the loop is your X coordinate, and the distance to the sum is your Y coordinate.

But wait. Earlier I said “if you know how many diagonals there are.” How do we know how many diagonals there are, for a matrix of a given size?

Turns out it’s really easy: width + height - 1. That works for all matrixes of all sizes.

So here’s an approach that will generate correct values for the first few diagonals, but not the rest:

// WRONG: This doesn't work, but it's a start

final width = cols.length;

final height = rows.length;

final Iterable<Iterable<int>> diagonals =

Iterable.generate(width + height - 1, (diagonalIx) => {

final sum = diagonalIx; // I ♡ unnecessary variables

// For any positive integer N, there are N+1 pairs of integers >= 0

// (including reversed pairs) that add up to N

return Iterable.generate(sum + 1, (coordinateIx) => {

final x = coordinateIx;

final y = sum - coordinateIx;

return rows[y][x];

});

});

Iterable.generate takes two arguments: the length of the iterable you want to generate, and a function that accepts an index and returns the corresponding element.

The problem is that, starting on the fourth diagonal, we don’t start counting at 0. The first coordinate there is (1, 2). Also starting on the fourth diagonal, we lose the nice pattern where each diagonal is an element longer than the previous one. This sucks.

After talking it over with my math-smart wife and puttering around the kitchen for a while, I had my next epiphany:

We know the size of the matrix. But if we assume it’s infinite, both rightward and downward, the length of a diagonal of index N would always be N+1. In other words, the first diagonal would have one element, the second would have two, and so on forever. And each diagonal would contain all the pairs of coordinates that sum to N. Once we have those, we can skip all the coordinates that fall outside the real (finite) matrix, and we’ll be left with just the correct ones.

And this was followed shortly by another:

If the number of coordinates in the (infinite) diagonal is greater than the width or height of the (finite) matrix, the difference will be the number of coordinates to exclude. The difference between the diagonal size and the height of the matrix will also be the starting point of the first coordinate’s X value.

Let me explain that better. Our original data set has 6 diagonals (go ahead, scroll up and count ’em). The sixth “infinite diagonal” would have 6 elements in it, but it only needs one (the number 12 at coordinates (3, 2)). Since the matrix has a width of 4 and a height of 3, we know there are 6 - 4 = 2 elements out of bounds on the right, and 6 - 3 = 3 elements out of bounds on the bottom. This makes sense because the matrix is wider than it is tall, so we run out of space vertically before we run out of space horizontally.

As luck would have it, 3 + 2 = 5, which is the exact number of elements we need to remove from the “infinite diagonal.” And since there were 3 elements out of bounds vertically, 3 will be the X value of the first coordinate. So the first coordinate will be (3, 2) (because the index of this diagonal is 5, so all coordinate pairs need to sum to that), and then we’ll stop because we have enough coordinates.

Here’s what this looks like as a nice, reusable Dart extension:

import 'dart:math';

extension DiagonalEx<T> on Iterable<Iterable<T>> {

Iterable<Iterable<T>> get uphillDiagonals {

final rows = this;

final height = rows.length;

final width = rows.first.length;

final numberOfDiagonals = height + width - 1;

return Iterable.generate(numberOfDiagonals, (diagonalIx) {

// Start by assuming the grid extends from (0, 0) to (Infinity, Infinity)

final numberOfCellsInInfiniteDiagonal = diagonalIx + 1;

// Then use the height and width to count the cells out of bounds

final cellsOutOfHorizontalBound = max(

0,

numberOfCellsInInfiniteDiagonal - width,

);

final cellsOutOfVerticalBound = max(

0,

numberOfCellsInInfiniteDiagonal - height,

);

final numberOfCellsInBounds =

numberOfCellsInInfiniteDiagonal -

(cellsOutOfHorizontalBound + cellsOutOfVerticalBound);

return Iterable.generate(numberOfCellsInBounds, (coordinateIx) {

final coordSum = diagonalIx;

final startColX = cellsOutOfVerticalBound;

final colX = startColX + coordinateIx;

final rowY = coordSum - colX;

return rows.elementAt(rowY).elementAt(colX);

});

});

}

// Don't read this part yet, it's a surprise

Iterable<Iterable<T>> get downhillDiagonals {

return map((row) => row.toList().reversed).uphillDiagonals;

}

}

iterable.elementAt(index) is equivalent to array[index].

He did it in under 50 lines of code! He did it without any if statements or for loops! The crowd goes hog wild! They blow the roof clean off! It’s blood and popcorn from wall to wall!

✅ Diagonal view

Back to regular, mundane horrors

Astute readers may note there’s more than one direction to be diagonal about. We’ve only solved ↗ uphill diagonals. What about ↘ downhill diagonals?

Luckily, we don’t need to implement that one, because downhill diagonals are just uphill diagonals in a mirror. Reverse each row of data and use the method you’ve already got.

import 'dart:math';

extension DiagonalEx<T> on Iterable<Iterable<T>> {

// ...

Iterable<Iterable<T>> get downhillDiagonals {

return map((row) => row.toList().reversed).uphillDiagonals;

}

}

In a Dart extension method, you don’t ever need to write this.. So map() refers to the .map method of Iterable<Iterable<T>>, which does exactly what you’d think. Sigh…I love Dart so much.

This felt right to me as soon as I thought of it, but I had to sit cross-eyed for a few minutes before I was sure. I wrote some unit tests to double-check, too. It’s legit.

✅ Diagonal view (the other kind)

And that’s all the directions I can think of! Good night.